This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. Fed chair Jay Powell sounded unbothered on Friday, telling an interviewer: “You won’t hear us overreacting to these [past] two months” of higher inflation. With a hint of braggadocio, he added: “We’ve divided our critics into equal-sized piles at this point”. His cool tone could be forgiven. Powell is tantalisingly close to securing the soft landing, and his legacy. Disagree? Email us: robert.armstrong@ft.com and ethan.wu@ft.com.

The fiscal impulse

It is widely agreed that US fiscal deficits are lifting both growth and the stock market, a phenomenon known as “fiscal dominance” (we have also heard “fiscal aftershocks” and “fiscal incontinence”). The idea is that the traditional, balanced relationships between the market, Fed and economy are being overwhelmed by fiscal force. The intellectual appeal is clear — the fiscal story simultaneously explains why there was no recession, why inflation remains a bit sticky, why long yields are still high, and why stocks don’t care about those higher yields.

The economic intuition for this view derives from the Levy-Kalecki identity, which holds that bigger government deficits must translate to higher corporate profits, if there no major changes in investment, private savings or dividends. Those higher profits then raise stock prices. The identity is easy to state — it’s just accounting — though in practice teasing out the deficit-to-profits causation can be hard. But deficits around 6 per cent of GDP outside of a crisis are rare, and it would be surprising if that didn’t affect the economy.

Recent big-dollar legislation, such as the Inflation Reduction Act and Chips Act, add to the suspicion. Since January 2022, US manufacturing construction spending has grown at a 52 per cent compound rate. And perhaps unsurprisingly, the government contribution to GDP growth has been higher than usual:

But here’s a wrinkle. Popular measures of the “fiscal impulse” — the incremental addition to the growth rate from fiscal policy — are not far from zero. Here is one widely cited index from the Brookings Institution. Far from lifting growth, it suggests fiscal has acted as a mild drag in the first quarter of this year:

The way to square this is to remember that fiscal impulse is a second-derivative measure; it tells you about changes in growth, which is itself a rate of change. It takes deficits widening to get growth to accelerate. A high but flat deficit can still put a floor under demand, but it can’t supercharge growth beyond the economy’s underlying “potential” growth rate.

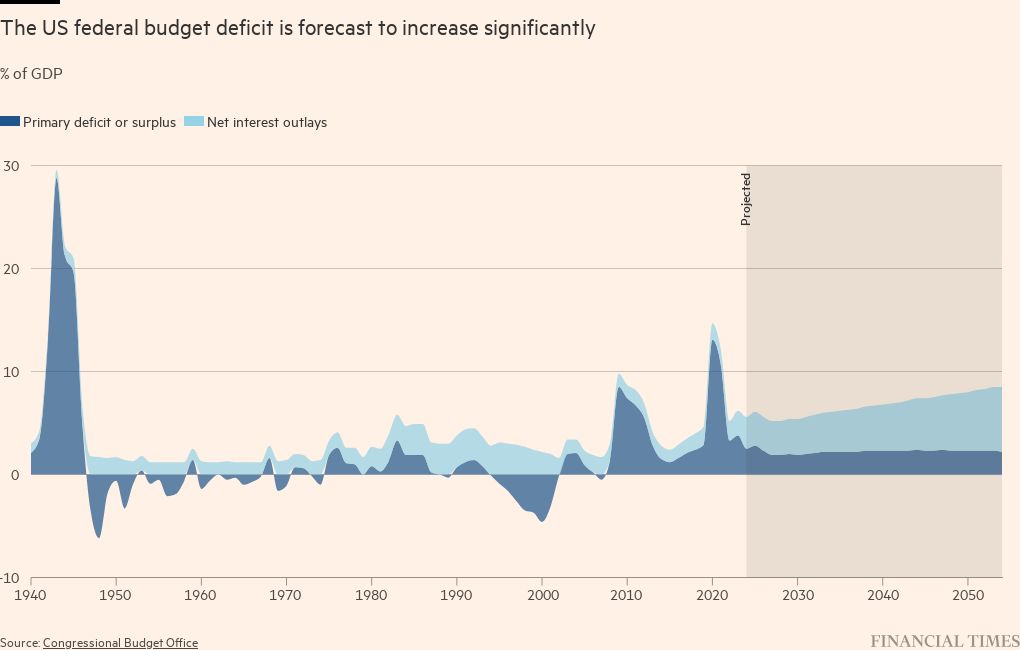

At this point a careful reader might reasonably wonder, wait, aren’t deficits in fact growing? The answer is yes, but mostly because of interest expense. As the chart below shows, primary deficits (ie, ex-interest) are set to stay stable as a share of GDP even as interest payments rise:

This matters because primary deficits have a different macroeconomic impact than government interest payments. Traditional deficit spending borrows from investors to, say, build a bridge; the money earned by construction workers then flows back into the economy. But when money is instead borrowed to pay ever rising interest expense, consider who is on the receiving end: duration-matching investors, bond funds, foreign governments. They do not necessarily turn around and spend their interest income on American goods and services. Their “propensity to consume” is low, in other words. Rising deficits driven by interest expense, rather than a widening primary deficit, are less stimulative.

The result: even though headline deficits will rise, the impact of government spending on growth may now be turning negative. Ian Shepherdson of Pantheon Macro points out in a recent note that the astounding growth rate in manufacturing construction is slowing, from more than 80 per cent year over year in mid-2023 to 37 per cent in January. Meanwhile, state and local (S&L) government construction spending also fell 1 per cent in January, the first monthly decline since August 2022. Shepherdson argues that declining S&L tax revenue augurs poorly for future S&L spending, as this chart shows:

It’s a reminder to investors that markets are sensitive to changes, not levels. Even in a fiscally dominant regime, dominance can fluctuate. Markets appear optimistic about growth, but if the fiscal impulse flips durably negative, it will test how deep those convictions really run. (Ethan Wu)

The great British bargain stock, part III: replies

Last week I wrote that while UK stock indices looked very cheap — even cheaper than is justified by the UK market’s tilt towards old-economy sectors — I struggled to find individual stocks that looked like bargains.

Two managers of UK stock funds wrote to say I was not looking hard enough.

Alex Wright, who manages Fidelity International’s UK Fund, says he often looks for like-for-like comparisons between UK stocks and roughly equivalent stocks from elsewhere, where the UK half of the pair is at a discount. He sent me four such UK/US pairs: in Banking, Standard Chartered and Citi; in Homebuilding, Cairn Homes and Lennar; in Tobacco, Imperial Brands and Altria; in defence contracting, Babcock International and Lockheed Martin. In each case, either historical growth or anticipated future growth is much higher for the UK half of the pair, yet the stock is cheaper. Here’s the data he sent showing the contrasts:

I asked Wright what might be the catalyst for these valuation gaps to close. He suggested that M&A deal flow indicates that corporate buyers sees the value in the market: Spirent Communications and DH Smith both received multiple takeover bids last week at big premiums. It’s a matter of this enthusiasm spreading to equity investors.

Wright likes Stan Chart more than the similarly cheap Barclays because it has a better growth profile, attributable mostly to its exposure to Asia, where it has a strong rates and FX business. Since Bill Winters became the CEO in 2015, he has made the bank far less risky, he says.

Ben Russon, co-head of UK equities at Martin Currie, wrote to make the case for Barclays. It is trading at a 50 per cent discount to book value, whereas JPMorgan Chase, for example, trades at an 80 per cent premium to book. Here he makes the case that the stock prices in the failure of the bank’s recently announced strategic revamp:

Investors value banks on price-to-book value ratios with reference to the return on equity that the business can achieve. As Barclays has failed to consistently deliver an RoE in excess of their cost of equity, the shares have been valued at a large discount . . . the BARC management recently unveiled a multiyear capital return, RoE-enhancement strategy . . . It is obviously a leap of faith . . . whether these ambitions can be achieved. However, given the current valuation effectively reflects them not doing so, there is scope for meaningful share price appreciation if improvements are made from here

In addition to a share price that prices in the failure of Barclays’ strategy, Russon thinks higher interest rates, if sustained, will make the banking industry structurally more rewarding for investors. I agree. While in the short term the fast rise in rates could cause credit quality to decline, in the long run non-zero rates will, all else equal, increase industry margins.

I leave it to readers to decide whether there is any chance that Barclays’ latest strategic reboot has any chance of working. You can read the FT’s coverage of it here, here, and here.

One good read

How The Atlantic turned things around.

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, hosted by Ethan Wu and Katie Martin, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.

Recommended newsletters for you

Swamp Notes — Expert insight on the intersection of money and power in US politics. Sign up here

Due Diligence — Top stories from the world of corporate finance. Sign up here